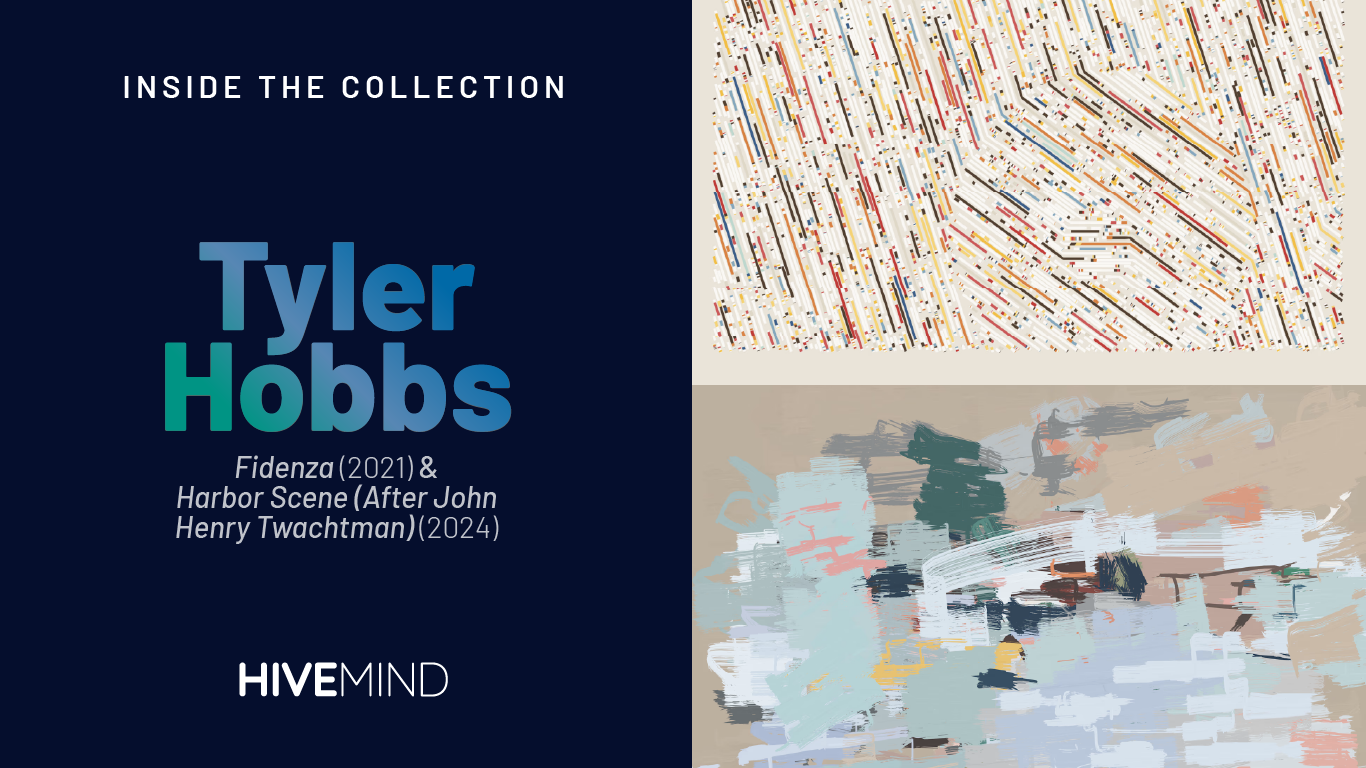

Inside the Collection: Tyler Hobbs | Fidenza (2021) & Harbor Scene (After John Henry Twachtman) (2024)

In the dynamic world of digital art, Tyler Hobbs (b. 1987, Austin, Texas) stands alone. With a subtle and adept hand, he combines his background in traditional art with his training in computer science to create works of digital art that suggest the continuity of art history across time and media. In this installment of Hivemind’s "Inside the Collection" series, we explore Hobbs's creative process and the interplay of past and future in his seminal series Fidenza (2021), as well as his limited series Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman) (2024).

Tyler Hobbs: Uniting Traditional and Digital Art

Hobbs holds a BS in computer science from the University of Texas at Austin and worked for many years as a software engineer; however, he also grew up drawing and has always found ways to express himself artistically. In 2014, he began experimenting with algorithmic art, using custom software to generate complex, abstract compositions. This innovative approach allows him to explore the intersection of computational design and visual aesthetics, resulting in works that merge the precision of code with the spontaneity of artistic expression. Throughout his career, Hobbs has advocated for the integration of digital tools into the creative process, believing that technology enhances, rather than diminishes, the possibilities for artistic exploration. His work stands as a testament to the fusion of old and new, inspiring a new generation of artists to embrace the limitless potential of digital mediums.

Hobbs is a creatively ambitious artist whose practice is constantly evolving because of his ceaseless experimentation. In a recent conversation with Hivemind, Hobbs explained: “Sketching is a mindset. It’s about getting myself into a place where I’m exploring and where failure is not only a tolerated outcome but an expected outcome.” He continued: “I sketch both on paper and in code. I tend to access different ideas in one format or the other. When I’m sketching by hand on paper, it tends to be more compositional ideas, and by that, I mean thinking about shapes and structure. Typically, when I’m sketching with code, I’m playing with simple patterns and algorithms. Those tend to be very surprising. It’s a very playful, exploratory, and open-ended mode.” Likes to see what patterns arise when he scribbles randomly by hand. He shared his sketchbooks with us, and they looked like a work of art in and of themselves. Writes an idea of the code schematically before he turns it into code. Lets the work become what it can.

Fidenza (2021)

Hobbs's seminal series, Fidenza (2021), showcases his ability to combine the unpredictability of generative art with the principles of traditional design. Through an algorithm with meticulously crafted rules and parameters, Hobbs produced 999 unique pieces. These works differ dramatically in their colors and forms, but what unites them is a sense of line and movement. In Fidenza, Hobbs worked with flow fields, an “algorithmic technique he popularized to produce surprising, organic curves with a precise, harmonious flow.”

Tyler Hobbs' Fidenza series is a landmark in the realm of generative art, showcasing his ability to blend algorithmic precision with artistic intuition. Created through custom software that Hobbs meticulously developed, each piece in the series is generated by a set of rules and parameters that guide the flow of complex, organic forms. The process begins with Hobbs defining these parameters, which dictate how shapes, colors, and patterns will interact. Once set in motion, the algorithm produces an array of unique compositions, each reflecting a balance between control and chance. Hobbs carefully curates the output, selecting pieces that resonate with his artistic vision, thereby infusing the generative process with a personal touch that transcends mere code.

The Fidenza series is deeply influenced by art history. Hobbs draws inspiration from mid-20th-century artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin, whose work focused on simplicity and geometric abstraction. Additionally, the organic, flowing forms in Fidenza echo the fluidity found in works by abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock, while the intricate patterns recall the mathematical precision of artists like M.C. Escher. By blending these influences with his own computational approach, Hobbs creates a dialogue between traditional art forms and contemporary digital practices, positioning Fidenza as a bridge between the past and the future of art.

Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman): Making a Mark

Hobbs has long found inspiration in art history, but never has he so explicitly explored the dialogue between traditional and digital art than in his 2024 limited series Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman). This project originated in 2023, when the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs invited trailblazing digital artists like Hobbs to create new works of art inspired by the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) through their “Remembrance of Things Future” blockchain initiative. Upon careful consideration of LACMA’s vast encyclopedic collection, Hobbs selected as his source material for this project the unfinished, c. 1900 oil painting Harbor Scene by American Impressionist artist John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902). Hobbs developed an algorithm and generated hundreds of outputs before carefully selecting three unique works that, to him, cumulatively embody the “essence” of Twachtman’s Harbor Scene in abstract terms. Of these three unique generative works of art, one is held in the artist's private collection, and Harbor Scene #2 (after John Henry Twachtman) is part of Hivemind’s Digital Culture Fund (figure 1). It is a privilege for Hivemind to have been entrusted with the stewardship of this work, which is singular in Hobbs’s oeuvre yet emblematic of his broader creative vision. A percentage of the proceeds from the sale of this work also benefited the LACMA Art + Technology Lab, which supports creative experiments at the intersection of art, design, technology, and industry. This project, therefore, marks a notable moment not just in Hobbs’s artistic career, but also in a major American cultural institution’s mission to support innovation in digital art. The institutional origins and recognition of Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman) have already solidified this limited series in the annals of art history.

In the late 19th century, Impressionism broke radically from tradition. Impressionist artists painted with improvisational, gestural brushstrokes en plein air, or outside, rather than carefully executing their compositions with a high level of finish inside a studio. Their goal was not to imitate the natural world but instead to convey the essence of a fleeting moment in time, impacted by numerous environmental factors but defined in large part by the changing effects of natural light. These artists often returned to the same subjects, painting them from the same perspectives and with similar cropping but at different times of day and year. A century later, generative art also broke radically from tradition. Generative artists today create their work using autonomous systems, running the same algorithms at different times and under various conditions to produce unique works of art, often in a series. Although the digital marks made by an algorithm typically differ dramatically from the gestural brushstrokes of Impressionist painting, these two art forms share their serial formats. They embrace spontaneity and randomness, yet underlying patterns and systems govern them both.

In Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman), Hobbs investigates the continuity between Impressionism and generative art in literal and figurative terms. He uses an Impressionist painting as his source material, but he also advances through generative art the themes first raised by Impressionism: spontaneity, chance, movement, gesture, body, process, and system. Operating within the systematic constraints of an algorithm, Hobbs aims to “arrive at a similar level of freedom and surprise” as Impressionist painting while allowing his work to evolve into something entirely new and specific to its medium. Indeed, while Hobbs borrows the pastel color palette of Harbor Scene and emulates its free, loose marks, his three abstract compositions otherwise deviate from their figurative source painting. Rather than depict a boat in a harbor, Hobbs aims in these works to “capture the essence of the water, the air, and the clutter of energy” that he associates with childhood memories on his family’s sailboat.

In Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman), Hobbs also emulates the “complex negative space” that first drew him to Twachtman’s unfinished painting. In a recent conversation with LACMA and Cactoid Labs, Hobbs spoke about his fascination with preparatory sketches and unfinished work. He described sketching as a “mindset,” which allows an artist to “jump into the exploration of an idea” before they have a “chance to overthink or overwork it.” He continued: “Unfinished work has this raw, exposed quality that makes it feel more personal.” While the unfinished nature of Harbor Scene calls attention to the artist’s hand and process, it also nods toward abstraction. The expanses of raw canvas and quick, sketchy brushstrokes, which become increasingly non-representational around the perimeter of the canvas, heighten the viewer’s awareness of the surface of the painting and foreground mark-making as the subject. These are hallmarks of modernism, taken up by artists throughout the 20th century, but principally by Abstract Expressionist painters in the 1940s and 1950s. One such painter was Joan Mitchell (1925-1992), whose work Hobbs has cited as inspiring his abstracted, gestural, and self-reflexive mark-making in Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman). Also among the Abstract Expressionist painters was another of Hobbs’s inspirations, Philip Guston (1913-1980), who often returned to the same colors and motifs in his work—creating an expressive array of figurative and abstract paintings within a controlled system. To this end, Hobbs’s Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman) is part of the continuum of art history. In a dynamic new language, it raises familiar questions about the process of artistic creation.

Conclusion

Hobbs’s body of work exemplifies how digital tools can extend and transform art historical paradigms. Fidenza is the defining series of his career, and Harbor Scene (after John Henry Twachtman) is a unique collaboration with a major cultural institution. We are thrilled to include 25 works from the Fidenza series, as well as Harbor Scene #2 (after John Henry Twachtman), in Hivemind’s Digital Culture Fund collection. You can view that collection here.